|

Become

a fan on Facebook

Become

a fan on Facebook  Follow

on Twitter Follow

on Twitter

Article by Mark Dujsik | December 26,

2016

Here

are the ten best films of 2016:

10.

The

Handmaiden 10.

The

Handmaiden

This

invigorating exercise in shifting perspectives and sympathies tells the story of

con artists in Japanese-occupied Korea during the 1930s. These are characters

who attempt to lie, cheat, and steal their way into the heart of another person,

only to discover that they have cheated—or have been cheated—themselves. It

would be unfair to disclose the exact number of con artists in The Handmaiden. Part of the enjoyment of co-writer/director Chan-wook

Park's film is discovering the extent of deception happening in front of us and

behind the scenes. What can be revealed without giving away too much is that

Park and Seo-kyung Chung's screenplay (based on Sarah Water's novel Fingersmith)

is divided into three parts. Each part reveals a new layer deception, as well as

an assortment of moral and emotional contradictions. It's a sensual film, not

only in terms of its frankness about sex but also in its gorgeous aesthetic

qualities. The film's central concern is with the motives behind the overlapping

cons, allowing us to see these characters as the paradoxical entities that they

are—capable of both giving pleasure and inflicting pain. In this film, those

two states are interchangeable. It all depends on one's perspective.

9.

Tower 9.

Tower

Everything

one would expect from a film about a historical event is present in Tower: talking heads, archival photographs, news reports, and

dramatic recreations to fill in the narrative gaps. Even so director Keith

Maitland's film is a daring

piece of documentary filmmaking. The recreations have actors play the people

involved in the 1966 murders at the University of Texas, where a man killed 14

people (including the unborn child of an 8-months-pregnant woman) and wounded 32

others while holding a position on the observation deck of the tower in the

university's main building for over 90 minutes. Those actors are then animated

through rotoscoping. The effect is intentionally unnatural. It is distancing but

never distracting. That distancing effect is clearly intentional, too. We are

witnessing something that we could never truly understand what it's like to

experience. It also challenges the notion that violence like this, which happens

with more frequency now, is seen as normal. The narrative jumps between the

accounts of the survivors, as we hear and see harrowing stories of pain and

courage. The film's power is in its clear-eyed documentation of what happened

that day, and it's also in the deliberate juxtaposition of cinematic form and

reality.

8.

Hell or High Water 8.

Hell or High Water

The

combination of desperate men and desperate times leads to an inevitable result

in Hell or High Water, a

cops-and-robbers drama that makes room for sympathy for both sides. This is a

film about life-and-death situations, a race against time, and the effects of

the financial crisis on ordinary folks. It's also a film, though, that will put

all of these concerns on hold in order to portray the mood and tenor of this

place—West Texas—and the people within it. Billboards announce "debt

relief" and other promises of returning to financial normalcy. A waitress

at a local diner has a particular way of taking orders, while a man at another

diner waxes philosophical about the absurdity of robbing banks in this day and

age. The robbers are brothers Toby (Chris Pine) and Tanner Howard (Ben Foster).

The cops are Texas Rangers Marcus Hamilton and Alberto Parker (Gil Birmingham).

Screenwriter Taylor Sheridan gives us a sense that the parties could have a

pleasant conversation over a steak dinner under different circumstances, while

director David Mackenzie establishes an inescapable backdrop of small-town

poverty, based on a broken a system and shattered promises. This is a simple but

perceptive, morally ambiguous, and detailed piece of storytelling.

7.

Krisha 7.

Krisha

Nobody

sets out to become the villain, and no one sees himself or herself in the role

of the villain in one's own story. Krisha (a tremendous Krisha Fairchild), the

eponymous central figure of writer/director Trey Edward Shults' debut feature

film, is about as close to fulfilling the role as a person can when at a family

Thanksgiving dinner. The character was an addict, who has been away from her

family to get healthy. Now, she has returned into the fold, and Krisha follows the increasingly uncomfortable events from her

perspective. Shults' camera simply, expertly moves with Krisha as she attempts

to maneuver her way into a sense of normalcy with her family again. It's a

dizzying experience, as the character's paranoia about the family's thoughts

about her become our own suspicions about them and Krisha. There's a connection

between the film's fiction and the reality of Shults' life (various family

members play the family members in the film), which might explain why all of the

film's elements are so deeply felt and clearly communicated. We can understand

the family's trepidation about having Krisha around, and but we're invested in

and sympathetic toward Krisha's gradual realization that she is both the

destructive antagonist the wounded protagonist in her own story.

6.

Green Room 6.

Green Room

Here

is a ferocious, relentless thriller. Jeremy Saulnier's Green

Room gives us characters who are capable of mistakes and puts them into

circumstances in which one mistake can have lethal consequences. The plot is

simple: A struggling punk rock band takes a gig at a neo-Nazi club in the middle

of nowhere, because they are in desperate need of money. Pat (the late Anton

Yelchin) comes across the scene of a murder in the club's green room, leading

the band to be imprisoned in said room. What unfolds is more or less a battle of

wits between the quick-witted prisoners who have limited resources to employ,

and their captors, who possess seemingly unlimited resources but are cautious to

use them immediately. That's because Darcy (an icy Patrick Stewart), the gang's

leader, wants to stage the witness' murders as accidents. With this film,

Saulnier shows himself to be in the process of becoming one of our more

effective and considerate filmmakers when it comes to violence. There are always

repercussions to the story's brutally violent acts, so while, on the surface, the

film is a crackling potboiler with a fatalistic sense of forward momentum,

it also deals with the inconsistent beliefs of the senselessness of violence and

the at-times necessity for it.

5.

Gleason 5.

Gleason

Former professional football player

Steve Gleason was diagnosed with Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS),

otherwise known as Lou Gehrig's disease. The effects of the disease are

terrifying: As it progresses, voluntary motor functions shut down, inhibiting

and eventually stopping one's ability to move and speak. Gleason is an example

of how multiple layers of courage can exist in one individual, and the mere

existence Gleason, a documentary from

director Clay Tweel about Gleason's life with ALS, reveals a significant layer.

Through a series of video journals and footage of Gleason's home life, Tweel

assembles a portrait of a man—a husband, a father, a son, a celebrity, a

philanthropist—that does not intentionally hide or inadvertently obfuscate a

single detail of Gleason's life. That includes the effects of the disease.

Shortly after his diagnosis, Gleason learns that his wife Michel is pregnant, so

he records video diaries as a way to pass on lessons to his son. The journals

are where the film is at its most intimate. Gleason doesn't hold back on

expressing his doubts and fears. He wants his son to know him—all of him. This

includes him breaking down in tears after he watches some of his old entries,

realizing that he sounds "ill." The film doesn't sugarcoat any of

this. There's nothing noble about illness, but there is nobility in how some

people approach the reality of it.

4.

Sing Street 4.

Sing Street

Sing

Street may only be about "this kid, a girl, and the

future," but that's just a simple way of saying it's about everything that

matters. Writer/director John Carney's equally delightful and insightful

film delves into the constant pangs and limitless possibilities of adolescence.

The setting is Dublin in 1985. Ireland is in the midst of an economic crisis.

These are the trying times in which the 15-year-old Connor (Ferdia Walsh-Peelo)

finds himself, as his parents, in order to save money, send him to a local

Catholic school filled with strict rules and rough bullies. Connor's only escape

is music—namely the new wave bands of the decade. The girl is Raphina (Lucy

Boynton). He decides to start a band in order to impress her. Carney starts with

nostalgia for this place and time, but he doesn't stop there. The film allows

its characters to live and breathe as far more than just representations of a

lovingly recalled time. Carney's affection and empathy for these characters

seems to have no limit, as Connor slowly realizes that there is much more to the

people he knows—himself included—than what he sees on the surface. As for

the film's music, the original songs accurately ape the style of the era and are

especially catchy. Like the characters, the music evolves, and Carney

effortlessly uses it as a way to communicate what's happening in these

characters' lives.

3.

Moonlight 3.

Moonlight

Moonlight is

a coming-of-age story about one person within the context of three, specific

stages of his life: as a boy, a teenager, and a man. Writer/director Barry

Jenkins' film is uncommonly attuned to the way that experiences shape everything

about a person. Through three tremendous performances—one for each of the

stages of the man's life—that somehow coalesce into a singular whole, we can

spot the obvious differences and the subtle similarities in this individual as

his life progresses. The character's name is Chiron. As a boy, he is called

Little (Alex Hibbert). As a teenager (played by Ashton Sanders), he has

reclaimed his birth name. As a man, he calls himself Black (Trevante Rhodes),

after a nickname someone else gave him as a teenager. This is a story of

definitive moments and influences that only become so in retrospect. Some of

these influences include his mother (played by Naomie Harris), who is only as

present in his life as a drug addict can be, and Juan (Mahershala Ali, whose

performance makes such an impact that the character's presence remains even

after he is absent from the story), a drug dealer who imparts crucial lessons

and an even more influential example. The film is filled with a sense of

constant discovery—of the character learning about himself and the world, of

us witnessing that character's evolution in unexpected and delicate ways, of

seeing the emergence of Jenkins' uniquely bold and boldly confident voice as a

filmmaker.

2.

Jackie 2.

Jackie

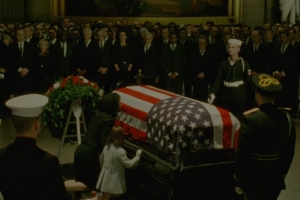

President

Kennedy has died. Mrs. Kennedy remains. It's a simple question at the heart of Jackie:

Now that her husband is dead, who is Jackie Kennedy? The Jackie of director

Pablo Larraín's film, played with courageous emotional honesty by Natalie

Portman, certainly doesn't know. Even in death, her husband and his influence

still hold a tight grip on this woman. Noah Oppenheim's screenplay is not a

biography of the former First Lady. It's a character piece that takes three

moments in Jackie Kennedy's life and plays them against each other. The first is

an interview with an unnamed journalist (Billy Crudup) about a week after the

President's funeral. The second is a filmed tour of the White House in 1962,

after the completion of an extensive restoration of the residence overseen by

the First Lady. The third is the three-day period between Kennedy's

assassination and his funeral.

That

section of the story is the film's central one. It is about Jackie's shock,

grief, and uncertainty, as well as her determination to ensure that her

husband's funeral is the one she believes the man deserves. The

conversation around Kennedy has turned from policy to legacy. The film is wise

in the way it sees Jackie as a constructor of narratives, building her husband's

legacy despite the knowledge that his presidential accomplishments are slim, and

it's tragic in its recognition that those narratives have little to do with her. She

has become a symbol of grief. Portman's performance and

the film as

a whole chip away at the shell of that icon of decorum and pity, presenting us

with a more comprehensive understanding of her grief, strength, and

foresight.

1.

Manchester by the Sea 1.

Manchester by the Sea

Writer/director

Kenneth Lonergan's exceptional Manchester by the Sea, the best film of 2016, isn't just about grieving.

It's also about how we avoid grieving—or at least try to avoid it. Lee

Chandler (Casey Affleck, revealing a meticulous understanding of how fear can

look like stubbornness, anger, and apathy) has lost his brother. He wants to

avoid this pain, because this death raises the terrible memory of the worst pain

of his life. Patrick (Lucas Hedges, in a performance so understated and

with such a seemingly unflappable sense of confidence that the character's

displays grief are all the more potent) has lost his father. He wants to avoid

this reality, because, as a teenager, he's not supposed to be experiencing this

at this point in his life. Lee's brother (played by Kyle Chandler) has made him

Patrick's guardian. Lee does not want the responsibility.

Lonergan's

screenplay is more or less a series of such vignettes, tied together by Lee and

Patrick's respective reactions to Joe's death, as well as the ebbs and flows of

their new life together under one roof. It also gradually reveals Lee's life

before the events of the present-day story, with a seamless structure that

intercuts the characters' current trials with an unthinkable tragedy from the

past (Michelle Williams plays Lee's ex-wife, and her performance within only a

handful of scenes is heartbreaking). What Lonergan focuses on is the strange

sense of socially prescribe routine that accompanies the grieving process—the

hospital, the funeral arrangements, the visitations and services and receptions.

The empathy displayed by the film—for these characters' struggles with

new pain and old heartbreak—is abundant and seemingly endless. Lonergan's film

is a marvel of compassion and character-specific observation.

Special

Mention:

Only

Yesterday Only

Yesterday

Twenty-five

years is a long time for a film from a studio as prestigious as Studio Ghibli to

finally receive a theatrical release in the United States, but such was the case

with Only Yesterday. Isao Takahata's animated film is a lovely examination of

the difficulties of childhood and the struggles of adulthood, as seen through

the eyes and memories of a woman who is still figuring out her life. The lessons

she learned from childhood and the realities of her life as an adult don't

exactly match, but they rarely do. That's the protagonist's predicament, as the

film's story shifts between two times in her life. Takahata differentiates the

two visually, with brighter scenes of the past that play out against incomplete

backdrops and naturalistic present-day scenes that are boldly colored. The

memories are of fairly ordinary concerns—young romance, puberty, and familial

dynamics—while the woman in the present attempts to piece together some

meaning from them. The film positions all of these events, not as answers or

explanations, but as a reminder that the process of growing up doesn't end with

the end of childhood.

Honorable Mention:

Arrival,

Cameraperson, The

Conjuring 2, Embrace

of the Serpent, Fences, The Invitation,

La La Land, Land

and Shade, Little Men,

Lo and Behold: Reveries of the

Connected World, Louder

Than Bombs, Neighbors 2:

Sorority Rising, Silence, Southside

with You, Weiner, Zootopia

Copyright © 2016 by Mark Dujsik. All

rights reserved.

Back

to Home Back

to Home

|

Buy Related Products

|